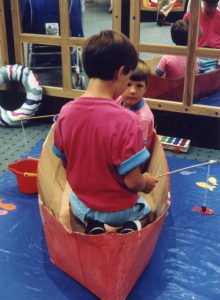

Playspace exhibit in The Psychology

Exhibition

One of my favorite blogs is Museum Questions, posted most Mondays by Rebecca Herz. I read her February 27, 2017 post, “Why Are Children’s Museums Museums?” with even greater interest than usual for a couple of reasons:

First, during the late 1980s into the 1990s–the period that Rebecca is examining in her post–I was involved developing a traveling exhibition (Psychology) for the American Psychological Association (APA) that helped to spread the Playspace exhibit at the Children’s Museum in Boston (BCM) to science and children’s museums in the US.

Second, because of that work I have questions about some of the observations about young children and learning that are contained in the post, specifically:

-

That it is primarily the adults who are learners in interactive exhibits like Playspace (according to Michael Spock).

-

That children’s museums, as Rebecca says, “focus on interactivity over content,” therefore undermining the experience as a museum experience: “somehow, between the early 20th century and now, we have gained popularity but lost something important. How can we cultivate a love of museums when children’s museums have little relation to art, history, or natural history museums? How can we teach problem solving when we don’t present problems? How can we teach information when we don’t curate around a big idea?”

I’m not an expert on the evolution of children’s museums, nor on programs and activities appropriate for older children. However, my years with Playspace, and my study of the role of play in the development of the exhibition Invention at Play lead me to make these comments, and they are mainly about children 5 and under in museums:

-

Parents/caregivers are not the only nor even the primary learners in Playspace or other interactive children’s exhibitions. The idea that adults were the learners and children were the exhibit allowed then-Children’s Museum Director Michael Spock to justify this space-without-displays as appropriate for a museum. While it’s true that the space in the original exhibit, and in our traveling version, was set up to provide all kinds of learning and support for accompanying adults, the key audience is the children. In the menu on this blog you can find further information on the purpose of Playspace in The Psychology Exhibition, and on the resources APA provided to make it a success at each host institution.

-

Water tables, sand tables, climbing structures, etc.–found in the original and traveling Playspace and, I gather, now in many children’s museums—are not simply for the development of gross motor skills. Developing gross and fine motor skills is in fact a part of children’s learning; but in pouring water, measuring sand in cups, creating hiding spaces in climbing structures, children are learning the characteristics of matter, the science of liquids and solids, the possibilities of their imaginations. These competencies are the bases for engaging in science and in art. Through them children are indeed engaged in problem solving at their level. The objects and activities in Playspace were created based on research and understanding of the developing human child; were intentionally chosen; and were specifically designed, or purchased because of their design, to encourage and promote developmentally appropriate learning.

-

It is not really necessary to add art, natural history specimens or other “content” to exhibits like Playspace. In a certain sense the play (physical and mental engagement) engendered by carefully chosen exhibit/activities is the content.

-

I think that some of the change in exhibits and collections for children’s museums comes out of a societal shift in how children are understood. In the 19th and early 20th centuries there was still a sense that children were little adults, smaller in stature but operating pretty much like their elders. Developmental research beginning with Vygotsky and Piaget in the ’20s and ’30s and continuing throughout the 20th century showed us that children evolve in the ways that they come to understand and interact with the world; they learn differently from adults. Play and activity are serious business and are the primary means through which young humans (as well as many other animals) acquire knowledge and understanding of the world. Thus cases of objects, of great interest to adults, are less engaging for children who do not have experience and context for finding them meaningful and absorbing. This is not to argue against children’s museums having or displaying collections. The BCM developed around a collection and continues to use it. However, given the understanding that children learn in ways different from adults, collections must be displayed in developmentally appropriate ways.

Some historical context

An overview of the Psychology exhibition with Playspace in the foreground.

The Psychology Exhibition was created by APA in collaboration with ASTC and OSC. I was first the educator (1988-95) and then the project director (1995-99) for this initiative. ASTC toured the exhibition (to 14 locations), and OSC designed and built it. APA provided the content, which was focused not on the therapeutic aspect of psychology, but on psychological research – into memory, cognition, the brain, social interaction, human development, etc. You can find more information on this exhibition here on this site, by clicking on Psychology Exhibition in the menu above.

Caryl March, the first project director for the exhibition, was a trained psychologist as well as a museum professional. In planning for the exhibition in the 1980’s, she found that the Children’s Museum’s Playspace had tremendous potential to present to visitors current research and understanding about child development. With designers at OSC we spent several years visiting, observing, and studying the exhibit, replicating but modifying it so that it could be part of a traveling exhibition on current research in psychology. Although many science museums fell in love with Playspace and wished they could continue such a space for their younger visitors after the traveling exhibition left, most were unable to sustain it because of the intense staffing demands. The original Playspace, as conceived by Jeri Robinson and as it continues today in Boston, is founded on a carefully curated combination of early childhood-trained staff, developmentally appropriate exhibits and activities, and parent-friendly design. Take away any of these three elements, and you don’t have the exhibit that Jeri created and that we traveled.

Three essential elements: staff, developmentally appropriate exhibits; care-giver support

I agree that there is a great deal of noise and seemingly aimless hyperactivity in the few children’s museums I have visited recently. I have also come upon slightly depressing spaces that have interactives designed for children. But they are unstaffed and provide little context for accompanying adults to understand what the kids, let alone older family members, are supposed to do. Both the original Playspace and the traveling version had the three-legged stool that I mentioned before as the philosophical foundation for the exhibit: trained staff (whether paid or volunteer); developmentally appropriate activities and exhibits; and all kinds of support for accompanying adults, from the comments and context provided by staff, to parenting resources (then in print but now maybe there could be info for caregivers to access on line) and simple, readable label copy explaining the value and significance of what their children were enjoying so much. As discussed above, none of this excludes the possibility of collections and objects as part of children’s exhibits; they just have to be presented with the same depth of developmental understanding as that which underlies the interactive exhibits.

Children’s museums are museums

Finally, I think the ever-expanding definition of a museum published on the website of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) leaves plenty of room for children’s museums. This definition has evolved from a narrow description of institutions that collect, conserve, and exhibit to a definition that includes public, non profit organizations that preserve, display, and educate society about its tangible and intangible heritage. Within this generous framework children’s museums have a role to play in introducing their youngest visitors to learning experiences, and their adult visitors to the intangible treasure that is a child’s mind.

Some resources

A wonderful blog about children and learning in museums is Museum Notes by longtime children’s museum expert Jeanne Vergeront.

My go-to study on how children learn is a chapter in How People Learn by John Bransford et al. (Bransford was a consultant on the Psychology Exhibition). You can read the book online or download it from the National Academies Press site. Chapter 4, “How Children Learn,” can be very useful even though it is written with a teacher audience in mind.

If you are reading this by email and want to comment, please go to www.museumcommons.com. Or you can comment on Twitter to me @gretchjenn and/or to Rebecca @rebeccaherz.

I remember reading Rebecca Herz’s 2015 blog post, “Are children’s museums museums?” and here she says that children’s museum “curate experiences” not objects. As an educator at a children museum, I think this is a true statement. A lot is going on at a children’s museum, a lot hiding just below the surface!

Thanks for that observation, Brittany. I agree.