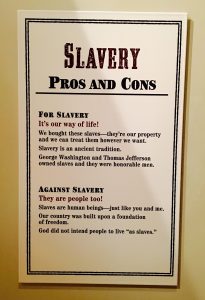

A museum’s attempt to be “neutral.” Is it? What questions does it raise? Photo by Stacey Mann

Where is Part 2?

In a post written on March 2, 2017, Stayin’ Alive, Part 1: Advocacy, I described efforts by the American Alliance of Museums, on behalf of the larger US museum community, to advocate for continued government funding of museums and cultural institutions in the face of a proposed Trump budget. As implied by “Part 1” in the title, and as I stated at the end of the post, I planned a second entry where I would examine a number of questions, including:

What is our role as cultural institutions during a time when a free press is denigrated, when xenophobia, racism, and intolerance appear to be on the rise and even encouraged by those in power, when the veracity of science is questioned?

Three months later I am still laboring on my follow-up post. I made up the question, and now I’m stuck. Upon reflection, the very question contains an assumption that for museums to work against xenophobia, racism, climate denial, etc is problematic–something new or challenging or out of the ordinary. Further, behind this assumption lurks the idea of museum neutrality, a concept that is reinforced every time it is decried, e.g:

Museums have traditionally been regarded as institutions that display factual, accurate, unbiased representations of culture….Something about mightily displaying otherwise inaccessible objects, complete with label placards and curatorial description, seems to scream attentiveness to actuality, furthering the idea that the museum is neutral as a displayor (sic)

Tanya Yorks, Graphite Journal (2009)

######################

Here at Eastern State Penitentiary we are rewriting our mission statement to remove the word “neutral.”We believe that the bedrock value that many of us brought into this field—that museums should strive for neutrality—has held us back more than it has helped us. Neutrality is, after all, in the eye of the beholder. At Eastern State, more often than not, the word provided us an excuse for simply avoiding thorny issues of race, poverty and policy that we weren’t ready to address.

Sean Kelley, Beyond Neutrality (2016)

Kelley’s post on AAM’s Center for the Future of Museums blog is, according to CFM Director Elizabeth Merritt, the most read piece ever published by CFM, having racked up 17,250 page views as of the end of 2016. The belief, not only that museums should be neutral, but that this is a core principle of museum practice, appears to be widely held. But where did it come from?

What does “neutrality” mean?

I think I need to address this idea of museum neutrality before any discussion of museums’ roles today. Most of the definitions I’ve read involve the idea of not taking sides in a conflict, e.g. Switzerland remaining neutral during World War II. Of course neutrality is also a position, but in the context of disagreement or opposing views it connotes non-involvement, non-endorsement of any single view. But don’t decisions to collect, display, or interpret x and not y require judgments and decisions on what is important, valuable, worthy of expense, time, and energy?

Museums are known for accuracy and for well-researched conclusions, but these don’t seem to me to be the same as neutrality either.

Neutrality and non-partisanship

It’s true that museums as non-profit institutions must be non-partisan, i.e. the IRS Code states that non-profits shall “not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing or statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) an candidate for public office.”

However, according to an article for the Council of NonProfits, not even all election-related activities are forbidden. The IRS allows voter education activities and public forums on elections as long as they don’t endorse a specific party. So the concept of “non-partisanship” is fairly narrow and literal, and does not exclude the kind of broadly educational programming that museums might organize around a specific issue.

Where is the concept in museum standards?

I don’t find the concept of neutrality in either AAM’s National Standards and Best Practices (2010) nor in any of the evolving definitions of “museum” published by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) over the years.

I talked about this with museum scholar Suze Anderson, blogger at Museum Geek, podcaster at Museuopunks and tweeter @shineslike at the recent American Alliance of Museums conference in St. Louis. Suze thinks the idea of neutrality comes out of the earliest origins of museums in the 18th century Age of Enlightenment and rationalism. Museums were seen as places where scientists and other scholars could display their collections, discoveries, and ideas. These were based on the scientific method and rigorous research, and therefore were objective and without bias, i.e. “neutral.” Cairns agrees that you won’t necessarily find this idea articulated in lists of best practice. It’s a long-held assumption that is deeply ingrained in museum culture despite the fact that simply selecting certain things and not others for display communicates a powerful point of view.

Perhaps what neutral means is “normative,” i.e. museums should reflect and represent–but not question–what already exists.

Although the assumption of museum neutrality may be time-honored, it seems to me that it was brought to the fore in a damaging way during the culture wars at the end of the 20th century, with contentious exhibitions such as Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment; The West as America; and Enola Gay. These exhibitions raised questions about long-held traditions and popular narratives and were criticized for having a specific viewpoint, i.e. lacking the desirable quality of neutrality. Perhaps what neutral means is “normative,” i.e. museums should reflect and represent–but not question–what already exists. Neutrality is often invoked as a reason not to exhibit or program around current issues, but is it really just an excuse for not offending anyone? And, as in the label reproduced at the beginning of this post, neutrality on some topics is offensive in itself.

What do you think? I’d like to continue to explore this question of museum neutrality, based on your observations and comments, or perhaps a guest post. I’d love to hear from readers who specialize in the history of the museum field. Is neutrality a core museum concept? Was it ever? What does it mean today as more museums examine their role in our fractured society?

If you are reading this post in an email please go to www.museumcommons.com to comment. Also you can send a tweet or DM me @gretchjenn.

Pingback: Intern Weekly Response: Museums and Neutrality

Pingback: Intern Weekly Response: Museums and Neutrality 2019

I’m sensing that this is a much more complicated question than we’ve given it credit for to date. It’s impossible to look at the issue of neutrality today without seeing the erosion of fact by opinion in almost every sphere of public discourse. Yes, it may be true that perfect objectivity is impossible in the affairs of human beings. But, for me anyway, that shouldn’t undercut objectivity and fact seeking as a value any more than the elusiveness of attaining human empathy and compassion should make us reject those values categorically. We are limited by our perceptions and biases, but that is no excuse for a wholesale rejection of accuracy as a goal, it is still worth striving for however unattainable it might seem. So I think we should be clear that when we reject neutrality, we are not rejecting methods by which information can be responsibly substantiated. No, we aren’t going to give creationism equal billing with evolution in some gesture of “neutrality.” No, we aren’t going to share the dais with “experts” who believe archaeology monuments were constructed by visitors from other planets.

Rolled up in this discussion is a term I have heard more often in museums than neutrality, which is “balance.” Balance cleaves more to the heart of the dilemma. For an example, I have seen museums attacked for including alternative perspectives on history as unbalanced when a counter argument could be made that including perspectives that were once marginalized IS the balancing. In these instances, you could say that presenting a perspective from outside of the dominant culture museums traditionally represent is a new kind of balance, one that is more inclusive. If curating means discerning, it might mean that curation enters a new phase where the selection of perspectives involves, among other things, weighing them both according to their legitimacy, but also as a way to get marginalized perspectives in front of more people.

Where it gets tough is when an outside-of-the-museum perspective really clashes with the “truth” as best we (museums) understand it. I think museums have worked through some protocols for this, for example trying to make distinctions between forensic truth, personal truth, social truth, reconciled truth. But, if you are a person who sees their truth being pushed to the curb, and today this is a growing number of people from all identities and political stripes, you get angry. It is highly problematic when recorded history and evidence has been saved and presented largely by archivists and historians who, until fairly recently, were only interested in documenting the narratives of the dominant class. A step away from “neutrality” towards “balance” should acknowledge the absent narratives in the historical record, moving towards trying to redress them. But this also means taking the heat when defenders invested in a previous narrative go into high dudgeon.

The other thing museums cannot get around is that many, many casual observers see attention paid by a museum to a particular perspective as some sort of sanction or emphasis, an official seal of approval. Yes, we can and should share authority. But we also have to choose whom we share authority with. I can’t see any way around that and this comes with a lot of responsibility. Museums will need to work very hard, leaning into their characteristic risk aversion.

The fact that museums have never been purely neutral, is a salient thing to accept. At the very least, museums espouse advocacy for their missions, to be champions for the disciplines they represent. This is no small matter, actually, especially in this age of dubious information and culture wars. A science museum can’t ethically pander to climate change deniers if science is the mission. This is not neutrality. Most history museums were founded in a spirit of national, local or civic celebration. Truth telling has not always found a comfortable place in these museums. If museums commit some sins of commission, they just as often commit sins of omission. For stories to make sense, details have to be both selected and omitted. Even the museums that pay tribute to more violent or traumatic aspects of our history, the memorials in particular, have tended to want to project a sense of triumph over adversity, of imposing unity on a story where the truth may actually be quite different. We seem to need museums to project “closure,” and this is not an act of neutrality at all.

Hi, Dan, I’ve not been checking this site as regularly as I should so just saw this. I agree with you about the difference between being neutral (or not) and hewing to standards of scholarship and accuracy. I just visited the Bible Museum in DC and am trying to wrap my mind around a post about it. The criticism that might have been made of this museum in the past, that it is not neutral, has been somewhat “neutralized” by this current discussion about no museum being neutral. So on what basis do I (we) critique the Bible Museum? The issues of scholarship and accuracy are very pertinent here.

Would you agree to my posting your thoughts on my blog itself? I think your comments add to the conversation. Thanks, G

Yes please!

Hi Gretchen,

I believe because I am not neutral, not are other people, museums can not be neutral, Sometimes they act neutral. This upset me most prominently a few years ago, 2009 when a Black security guard at Holocaust Museum was shot and very few museum on twitter seemed to acknowledge the murder or change their practice. I kept tweeting about it but no one I knew in museums really responded and I felt really sad. I had just stopped working in a museum because I wanted to find other ways with technology to talk about what I wanted to address, genocide, rape, domestic violence, exile, racism, antisemitism that I could not discuss at the museum I worked at in my positions and roles that I had at the time.. the culture wasn’t there. Thank goodness for #museumsrespondtoferguson and other initiatives the conversation became vocal. I thank all the people doing the work. I subverted my voice for a long time because I thought no one really cared.. I just dug in and drew the narratives I needed to share and took steps to create a museum and public garden but, now finding I may start to use my voice again because all of you are responding to how people in museum, at museums, and who wonder about museum feel, live and experience life. Better World Museum is utopian, but it is anything but neutral. Its a highly social and politically intentional space for empathy building, healing, and connection.

Hi, Paige, I haven’t been checking this site recently so missed this. Thanks for your thoughts and your personal experience. I think your Better World Museum is such a great thing, and hope you continue with it. Best- Gretchen

I agree with Lath’s comments that as we create exhibits we are always making choices about what to present and how to present it – Most visitors do not realize the amount of interpretation that goes into the exhibits they might assume are neutral. Beyond that, I found Colleen Dilenschneider’s post (https://www.colleendilen.com/2017/04/26/people-trust-museums-more-than-newspapers-here-is-why-that-matters-right-now-data/) about a large study of people’s views of trust in museums compared to government organizations and daily newspapers quite interesting. People, by far trust all kinds of museums far more than government and non-government organizations as well as daily newspapers. In very similar percentages, they find museums highly creditable – which might be interpreted as neutral. They don’t believe museums should have a political position BUT they do feel that museums could recommend action as long as it fits with their mission. Which leads to the question of whether some museums are starting to rethink their missions. I think this question of neutrality is going to evolve much further as we go through this next period of political craziness. I think that as museums become more integral parts of their communities – another direction of change for museums – they become increasingly important centers for gathering and becoming involved in the relevant conversations of our time.

Thanks for this comment and reference, Lynn. I agree that this whole issue of neutrality is undergoing a change and also that the trust that people put in museums is an aspect of this neutrality question.

But do the public want museums to be neutral? Our research suggest that museums could benefit from being more activist, with millennials saying that this would make museums more relevant to them.

Sure, older audiences prefer museums to be neutral but I think it really depends on the issue.

Details from our survey of 1000 Americans can be found here: https://www.museumnext.com/2017/04/should-museums-be-activists/

Thanks, Jim, I agree that there is no doubt an age difference in what audiences want out of museums. Unfortunately I think that many of the older group are the folks who sit on museum boards and so use this concept of neutrality to quell activist approaches. I’m looking forward to reading your study. thanks, Gretchen

It may be informative to look at the conditions in the field of cultural anthropology that lead to the rise of “cultural relativism.” Core to this was the idea that where their is a “map”, their is a “map maker” and this is a position that cannot be neutral. I actually can’t believe 30 years later we are still having this conversation. I’ve been creating exhibits for 26 years (map maker) and there are thousands of decisions in each project that are not neutral. If anything this is a failure of understanding by the public of what a museum is.

That’s an interesting idea, Lath. Thanks for this. Agree with you. G