[We propose a paradigm] for how museums address their responsibility for fair and inclusive staffing, collections, and interpretation, and equality of access to their resources. This paradigm will examine a vocabulary and a set of theories not usually found in current museum discourse:

Oppression: identifying the complex – and too often unacknowledged – ways

in which systemic structural norms influence decision-making so that cultural

institutions present themselves in ways that are unacceptable and exclusionary

to many.

Privilege: pervasive assumptions of whiteness and wealth, which are counter

to inclusion and diversity (and, in fact, perpetuate white cultural dominance);

Intersectionality: understanding how race intersects with gender, social justice,

class, and socioeconomic status.

Excerpts from the Statement of Purpose of Museums and Race 2016: Transformation and Justice, a convening held in Chicago, IL, Jan 25-27, 2016.

From July, 2015, through January, 2016, I was involved in planning this convening with a multi-racial, multi-generational, and multi-disciplinary group. During that period I came across some of the terms highlighted above for the first time. I observed that they were part of the everyday vocabulary of many of the younger planners and colleagues of color. Now, eight months later, these terms are integral to the way that I think and talk about museums. I come across the words everywhere, as often happens when we begine to “see” something that was there all the time. I want to share this language-learning experience with my readers because I believe that these terms are apt descriptors for the state of museums and race today, and that they can help bring clarity and understanding to a conversation that the field must have. So here goes part 1 of my Primer, in which we examine the term “privilege,” specifically white privilege.

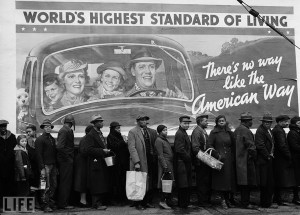

Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1937

The reading list on the Museums&Race2016 website provides several sources examining white privilege, but a number of us at the Convening agreed that this article by Peggy McIntosh is unequaled in its ability to communicate vividly the continuing nature of this phenomenon.

In Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack of White Privilege, McIntosh, a feminist scholar, describes her mental journey from the study of male privilege to the awareness of white privilege. With both groups, she observes, the holders of privilege do not view it as such; rather they see their way of being in the world as “normative, neutral, and ideal.” McIntosh writes:

I was taught to see racism only in individual acts of meanness, not in invisible systems conferring dominance on my group…

I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was “meant” to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks…

As far as I can tell, my African American coworkers, friends, and acquaintances with whom I come into daily or frequent contact in this particular time, place and line of work cannot count on most of these conditions:

- I can, if I wish, arrange to be in the company of people of my race most of the time.

- I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

- When I am told about our national heritage or about civilization, I am shown that people of my color made it what it is.

- I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

- I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.

- I can be sure that if I ask to talk to “the person in charge” I will be facing a person of my race.

McIntosh lists about 20 more examples in this article. Another piece contains over 50, including “I can worry about racism without being seen as self-interested or self-seeking” and “I will feel welcomed and ‘normal’ in the usual walks of public life, institutional and social.”

I thought it might be interesting to take McIntosh’s examples and apply them to museums. Here are a few that I (a white woman) came up with:

- If I am a white male invited to serve on a museum board, I can be certain that I will not be in the minority.

- If I ask to speak to the Director or other senior museum administrator I can be pretty sure it will be someone of my race.

- If my family and I walk into a museum we can be fairly certain to be greeted warmly by volunteers who look like us.

- If my family and I walk into a museum we can be pretty sure to see lots of other visitors who look like us.

- If I work in a museum and I get angry about a work issue, it will not be attributed to my race.

- If I visit an art museum I can be certain that I will see a preponderance of works by people like me, especially if I am a white man.

- If I visit a museum of American history, an historic house or plantation, I can be guaranteed that most of the exhibits will highlight the stories and contributions of people who look like me.

- If I visit a museum of natural history I can be fairly certain that people who look like me will not be displayed in dioramas of exotic cultures (other than dioramas of early humans).

- I can always find images of people who look like me and my family in museum brochures, advertising, web pages, and social media.

- I can be pretty sure that the person who leads me on a tour will look like me.

What examples can you add?

But awareness that most American museums are conceived in, operated according to, and powerfully resonate with white privilege is not enough. We must think about the impact that this long-lived and rich yet limited perspective (of which we as a white-dominated field are mostly oblivious) has on the work of all of us (white colleagues and those of color). In my view this aura of white privilege is more potent than any inclusive mission statement. It confronts visitors of color at the door if not in the parking lot (where the attendant may be the only person of color they see during their visit). It shapes the art and artifacts we collect, the stories we tell, the people we put on our boards, the candidates we hire, the flavor and content of our advertising and social media, the tone of our “community outreach.” No diversity policy by itself has enough depth of penetration or varied texture to shade this whiteness. Only an internal transformation of the field and of each museum will suffice: through new and different approaches to recruitment and hiring; through inventively inclusive collection, exhibition, and programming policies, through equal partnerships with individuals and communities of color. And through frank and respectful discussion.

The Museums & Race 2016: Transformation and Justice initiative is dedicated to building on and broadening the awareness of white privilege that our museum colleagues of color have critiqued and worked for years to change. We hope that others in the field will join our effort. Coming to understand a common vocabulary is a first step.

Look for future posts on museums and oppression, intersectionality, systemic racism, and other useful terms.

If you are reading this on email and would like to post a comment or question, please go to www.museumcommons.com or send me a tweet @gretchjenn. Thank you.

Gretchen,

Thank you for sharing your experiences from this convening. It is very exciting work and I look forward to hearing more about your reflections. As someone who started out in the early ‘90s in the YouthALIVE! Initiative issues of diversity have been of great interest to me in my work.

I was wondering if the subject of salary was discussed. In addition to other cultural and racial barriers, I think we have come to see that unless we start creating positions that offer a real living wage, we will still be limiting ourselves to people who can afford to work in the field.

Thanks again for all the great work you do and share.

Lynn

Hi, Lynn, at the Convening we focused mainly on race but we are closely allied with the #MuseumWorkersSpeak movement Do you know of that group? Am not sure if there is a Boston branch but there are groups in DC, NYC, and Chicago. this group has a twitter chat on Worker Wed, the first Wed of each month using hashtag #museumworkersspeak. The group is going to be presenting at a number of sessions and lunches at AAM. The Convening group is going to present at the Unconference sessions at AAM on the first day – Thursday May 26, and MWS is going to be presenting with us. Thanks for your interest. If you want to start or be involved in a #museumworkersspeak group in Boston contact Elissa Frankle at efrankle@ushmm.org or Alyssa Greenberg at a.green34@uic.edu. Thanks for your interest and support! G

Thank you, Gretchen, for introducing us to this common vocabulary we can use to better understand and dismantle structural racism in our institutions. The application of McIntosh’s examples to museums is especially helpful. Here’s one more we could add to the list:

As a parent of young children who may express their energy or enthusiasm in active ways, I can expect to be treated with respect by security staff who remind me of museum rules.

Thanks, Daryl, that’s a good one. It would be interesting to see how many other examples museum folks can come up with! G