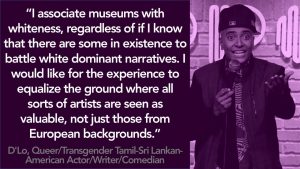

D’lo, Queer/transgender Tamil Sri Lankan-American

Actor/Writer/Comedian

Visitors of Color Tmblr

Can Museums Be Neutral?, a post by Museum Questions blogger Rebecca Herz, galvanized museum discussions on Twitter and Facebook in December, 2017. The conversation died down over the holidays, but I’ve continued to reflect on some of the important questions that were raised. Earlier in the new year I posted thoughts by Dan Spock on the topic, in which he argued that balance and accuracy must be part of the conversation..

There is not (yet) a single narrative on this issue. Those of us writing about museum non-neutrality are building a line of inquiry, not an air-tight definition. Continuing in this investigative spirit, I’d like to focus on one issue raised by Herz’s post: that neutrality presupposes a conflict in which one does or does not take sides. I believe that museums are indeed engaged in conflict. What is its nature?

Some might say that it lies in engagement with rifts in our society—racism, sexism, homophobia, the legacy of slavery, mass incarceration, income inequality, immigration policy. These are indeed divisive issues that some museums such as the National Museum of African American Culture and History , Eastern State Penitentiary and The Levine Museum of the New South have rightly taken on in exhibitions, programming, and public statements. However, there is a more basic source of conflict in our field: a conversation about the nature of museums themselves, It is here that we find the roots of our non-neutrality. And it is this conflict that we must address even while keeping our eyes on the wider world.

For insight, read the powerful introduction to the downloadable Toolkit for MASS Action: Museum as Site for Social Action. The authors locate museums’ origins in a particular world view that privileges a Western (and white) set of values regarding race, sex, and class. Beliefs in the primacy of scientific understanding, Enlightenment philosophies, and encyclopedic knowledge may appear to be self-evident and benign, but they are entangled with colonial “expedition, appropriation, and export” and the creation of a system of taxonomy. “The system makes claims on rationality but its biases and limitations are readily apparent.” That most museums, whatever their discipline or niche, come from this set of values means that they have already chosen (consciously or unconsciously) a side. “Museums do not just describe or collect cultural knowledge; they create it” (p. 12). It is for this reason that we can say that museums are not neutral.

Worldwide travel, immigration, the flight of refugees, global commerce—all of these mean that the racially, culturally homogeneous nation state (if it ever truly existed) is a thing of the past. Museums of all disciplines cannot continue to affirm a single narrative as the norm if they wish to remain relevant cultural institutions.

The current discussion about non-neutrality asks that museums

- Acknowledge the default position (described above) that most cultural institutions currently hold..

- Admit that they are indeed creating knowledge, not just displaying it; that their missions and collections reflect A point of view rather than THE last word. Art museum labels and catalogs, for example, should be more transparent about how and why they select some art/artists over others. Children’s museums should be aware that their assumptions about the value of play are culturally conditioned. They should present wider options diverse family participation..

- Take steps to move all of their organizational systems (Board membership, hiring policies, collections management, etc).toward inclusion, equity and justice, Museums must shift from practices reflective of a single dominant perspective to a more transparent and inclusive model.

In other words, museums must acknowledge that they already stand for what appears to many as an oppressive, unyielding, and exclusionary set of values. Museums must examine this stance, and they must decide if they wish to change sides. Cosmetic initiatives such as hiring a person of color for “underserved audiences” or bringing in a temporary curator on a diversity fellowship are not the answer. Real change requires systemic transformation.

The following are three initiatives that provide resources for this kind of intensive work.

The Empathetic Museum Initiative

I want to be clear that this post is not advocating that museums avoid or ignore current issues that affect their audiences. it’s my experience, however, that unless an institution is engaged in the internal work of inclusion and equity, its efforts to become involved in larger issues are likely to be reactive, patronizing, and sporadic. Museums that are deeply involved in their own self-reflection and transformation will contribute to our world in ways that are authentic, grounded, and sustainable. This is the kind of non-neutrality that we need.

If you are reading this post in an email and wish to comment, please go to www.museumcommons.com or send a tweet using #museumsarenotneutral to @gretchjenn. Thanks.

B

Thanks for adding this post to the ongoing conversation about museum neutrality. And YES to “building a line of inquiry not an air-tight definition”! Like you said, this all about defining what kind of museums we want — right now, and in the future. For museums, I think addressing this question of “neutrality” is a necessary step toward becoming an agent of change.