In a December 6, 2016 post Museum Geek blogger Suse Cairns asked this question: Can institutions be empathetic? My EM colleagues and I have been discussing the many thoughtful questions Suse has raised. Following is our response. We believe that it is possible for institutions such as museums to be empathetic, and below we outline the myriad possibilities.

Some clarifications

- As Suse observes in her first paragraph, “empathy” seems to be a trending term in museum discourse. But it is used in quite different ways by different colleagues. For example, The Empathy Museum project in Europe, and the recent book mentioned by Cairns, Fostering Empathy Through Museums, each focus on encouraging visitors to be empathetic, a laudable goal. The Empathetic Museum Project, however, is quite different in its intent. It looks at the very difficult yet (we believe) necessary challenge of developing institutional empathy, i.e. having structural policies and procedures (regarding Board composition, hiring, advertising, collections, etc) in place that create an empathetic and welcoming stance to those whom they serve.

- The idea of institutional empathy is actually an extended metaphor comparing institutions to the human body or person. All metaphors have their weaknesses, but we think this one is apt for the following reasons:

–It’s familiar: we often talk about the “head” or the “arm” of an organization; we might say that its mission is its heart or soul.

–It conveys the idea of a system, an entity whose parts are interconnected and interrelated. If you cut your little finger this will activate blood flow from the heart and pain reflexes from the brain; similarly what affects one aspect of an institution has an impact on all parts.

–Empathy, we feel, is a systemic quality; its effective communication and existence depends on consistency throughout the organism.

You can’t be a little bit empathetic.

- Suse quotes from Empathetic Museum writings: “museums are impossible without an inner core of institutional empathy,” but she omits some important parts of that statement. What we actually say on our home page is that the qualities that museums claim as the characteristics of 21st century museums–Visitor-centered. Civic-minded. Diverse. Inclusive. Welcoming. Responsive. Participatory–are impossible without an inner core of institutional empathy. Museums, in our view, can and do exist without empathy. But we don’t believe that museums can achieve the qualities they set for themselves as contemporary and relevant entities without institutional empathy.

Challenging Assumptions

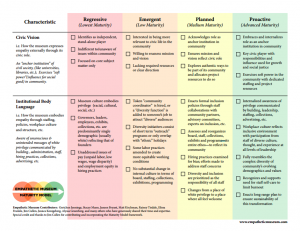

Suse is certainly right that there is a “Gordian knot” of traditional institutional structures–among them lack of transparency, hierarchical structures, and siloed departments—that work against empathy. (This Gordian knot metaphor reinforces the body/systems metaphor that we use.) It is precisely this tangled structure that we address in our Maturity Model, providing over 20 suggestions for concrete actions. These steps, presented as a rubric, provide guidelines to untangle, interrogate, and transform systems of white privilege, narrow and exclusionary collecting, monolithic board and hiring structures, colonialist legacies, and other traditional “best practices” that work against authentic connections between museums and their communities. In this respect, Suse’s treatment of diversity as a kind of add-on without which empathy is impossible ignores the centrality in our model of dismantling privilege, racism, and oppression. Suse’s main objection to the possibility of institutional empathy seems to be that it is difficult. We certainly agree, but believe that it is nonetheless worth working to achieve.

A page from our Maturity Model, charting practical steps toward Empathetic Practice

Finally, Suse asks who should be the object of empathy, and appears to believe that if an institution is empathetic toward some, it must ignore or short-change others. Empathy, like love, is not a zero-sum game. If you expand your circle of friends this does not lessen your love for your old friends. Empathy is not a pie that gives each person less as it is offered to increasing numbers. EM colleague Stacey Mann adds, “ This is my primary critique of the post: the notion of empathy as being pure equity 24/7. To my mind it’s more about being cognizant and intentional about the types of programs, exhibitions, staffing choices, etc. being made and holding ourselves to higher standards.”

And another colleague, Jess Konigsburg, writes “the concept of Civic Vision might be quite central to responding to Suse’s concerns. In particular, her comment: ‘To make lasting change has to mean working on the systems themselves, and not merely on the culture of the institution’ seems to suggest that she thinks a museum’s institutional empathy is focused exclusively on the institution and ignores other systems at play. In our description of Civic Vision, we talk about the importance of museums partnering with other civic institutions to use their combined influence to promote social justice and improve the community, thus informing how institutional empathy can and should influence other systems in the community. I also think Civic Vision could help address Suse’s concern about empathetic practice diverting resources away from existing constituencies. Civic Vision, to me, implies that when museums become more empathetic towards the needs of more and broader communities, they become better institutions for everyone (including existing constituencies). That is, if a museum thinks of itself as an anchor institution within the community, any changes or resource re-allocations that it makes should necessarily benefit existing communities as much as new ones.

“Another argument that Suse mentions in the comments section speaks directly to one of our core characteristics. Suse worries that empathy tends to be strongest towards those we share similarities with. Our characteristic of Community Resonance tries to address this concern by advocating for diverse hiring and Boards, thus helping to ensure that there are people in the institution equipped to empathize with a variety of groups.”

Suse’s provocative post has prompted us to clarify and articulate aspects of our thinking, and we are grateful to her for raising these important questions. We are continually updating and adding to our website as we receive comments and questions about our work. Coming soon will be more examples of empathetic practice, information on workshops and trainings that can assist institutions in developing empathetic practice, and updates on where we will be presenting at conferences in 2017. Here’s to continued conversation!

If you are receiving this post as an email and wish to comment, please go to this website. Or send a comment to Twitter @gretchjenn or @EmpatheticMuse.

I like this discussion a lot. Regarding institutions, a mentor once said to me that they tend to continually reproduce their way of being in the world (“culture”) over time and have seen that in play over and over again where I have worked. Resistance to even small changes that they even “say” they want to implement can be huge and the mechanics of it all are bigger than one or more persons. Also factor in the unconscious….so complicated.

I agree that institutions are change resistant, and I think this is one of the characteristics that makes Suse say that empathetic institutions are not possible. Maybe if institutions don’t start out empathetic they almost never can become so. It’s a daunting thought! G

Thanks Gretchen for the great post. One area I’ve been exploring recently is the field of universal design. One of the key principles of this design philosophy is, rather than focusing on design trade-offs, putting an emphasis on design for all. Here’s a site to explore. http://www.universaldesign.com/

Hi, Dan, yes I agree– design thinking is based in empathy, in trying to find out how and why people use a certain product or space and basing the design on that. I remember when I was working on Invention at Play, and we were using IDEO as one of our case studies. Their work definitely begins in an empathetic place. Also in looking at the work of the Stanford D school I think the same is true. It adds another element to empathetic practice. Thanks for reminding us all of this. G

Hiya. Thanks for the thoughtful response to my post. It helps me see where some of the gaps lie between what you’re thinking about and the work you’re doing, and how I’m looking at the same issues. My main objection to the idea of institutional empathy is not so much that it’s difficult as that institutions don’t work that way. It’s not in the nature of institutions, which are in many ways antithetical to personalized approaches to problem solving, to be empathetic. However, this perspective comes from my work studying institutions as institutions, not looking at institutions through a metaphorical lens. I suspect that this might be where some of the discrepancies lie. From what I can tell, you’re using the idea of empathy to speak about a set of values that you want to see museums adopt in order to become fairer institutions. Is that right? Whereas I’m talking about institutions as kinds of things, which have tendencies to act in particular ways, that do not necessarily align to human behaviours or desires. Also, it’s worth noting that I’m not speaking about individual institutions, but about institutions generally.

That said, there are further questions that your response brings up for me. For instance, you speak about empathy not being a zero-sum game, that “Empathy is not a pie that gives each person less as it is offered to increasing numbers.” However, a museum’s resources are often limited, even if the human aspects of empathy are not, so while you can be empathetic for many people at once, acting on that feeling is still about choosing where resources are allocated. This is inherently political, and I’m interested in hearing more about how institutions are resolving those questions. I suspect we agree on the aims and outcomes of what you’re trying to achieve, but differ on the use of language. Keep publishing more, and while I might still push back, I’m interested in the work you’re doing.

Thanks, Suse, this helps me better understand where you are coming from. Am rushing to get away for holidays so more later. All best for the New Year, and hope you have your mobility back as much as possible. G

Well written Gretchen and such important work to be done. I ask a question-do you think that museums that are founded by or serve underrepresented people (e.g. Chinese museum in NYC, Jewish museum in Philadelphia and Cambodian Museum in Chicago) have an obligation to diversify their boards and staff too? Would working collaboratively with others suffice? Can these types of museums be empathetic to all without a lot of diversity (not assuming they are not because I really don’t know so this is a hypothetical question).

This is a good question, Joan, and have just started thinking about it. I think it depends a lot on the community that such museums serve. If their audience is pretty much the same community as the board and staff then it would seem they are in a great position to be empathetic and in sync with those whom they serve. However, in some instances such museums may not be totally in sync for a number of reasons. For example the Louis Latimer House in NYC is now located in a neighborhood with many residents from China. Latimer was an African American inventor in the 19th century, and presumably when he lived in the house it was in an African American neighborhood. Now that area is changing, and I know from a recent administrator there that they have begun translating their materials into Chinese and hosting programs that still tell the story of Latimer but that also welcome the Chinese community. The Anacostia Neighborhood Museum has changed its name to the Anacostia Community Museum, and has brought on Latino staff to collect materials and host exhibitions related to growing number of Latino immigrants in the area. So these seem like empathetic moves for those institutions.