What is thinking systemically?

A system, as we know, is a group of interrelated and interconnected parts, such that what happens to one has an impact on all. I’ve been noticing, in all kinds of media, references to the importance of examining problems from a systemic point of view, i.e. recognizing that a problem is embedded in a complex network that must be untangled to be understood, let alone solved. Two examples:

- The film Spotlight reveals how the Boston Globe broke the story of the protection by the Boston Catholic Archdiocese of priests who had abused children. Early on, the reporters working on the story want to begin releasing details as soon as they have verified a number of cases. Editor Marty Baron cautions them to wait until they can document a pattern, and trace the protection to the office of the Cardinal, in order to show that this is not simply a collection of unrelated incidents but rather an organized effort to cover up multiple instances of child abuse by priests. The Globe ultimately published a story that exposed the system from top to bottom, winning a Pulitzer Prize, causing the resignation of Boston’s Cardinal Law, and sparking investigations of priestly child abuse that continue to this day.

- Evicted, by Matthew Desmond, is up for a number of awards and was on many “best books of 2016” lists. The author examines the web of adversity that eviction imposes on individuals and families. I again became aware of the importance of systemic analysis when I read this from Washington Post critic Carlos Lozada’s review: ” ‘Evicted’ does not traffic in tired arguments about race pathologies or family breakdown. Rather, Desmond identifies perverse market structures, destructive government policies and the cascade of misfortunes that comes with losing your home.”

I’d like to take these examples and use them to examine how we might understand the challenges that museums face around diversity and inclusion (D & I) by using a systemic framework. A number of colleagues are beginning to question the validity of these terms. See Porchia Moore’s Incluseum post on “The Dangers of the ‘D” Word.” Diversity and inclusion are often proposed as solutions or adjustments to the pervasive white culture of museums, which is presumed (unconsciously) to be normative. In addition to being off-putting to people who are not white, this set of assumptions leads to D&I strategies such as a temporary exhibition on Latino art here or the hiring of a “Community Coordinator” (usually a young woman of color) there. How might thinking about D&I from a systemic viewpoint move D&I strategies from “quick fixes” to transformative initiatives.

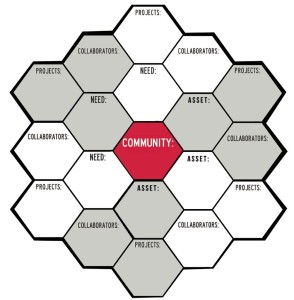

Image created by Nina Simon to illustrate the community-centered planning focus of her museum.

- Shift your systemic focus, moving to the center the community(ies) that you think have been excluded in the past. Think of these communities as “we,” not “they.” Begin conversations with them and ask for their help. Such overtures may be met with suspicion if they are unexpected and out of context. Be sure to find allies and proceed with respect and diplomacy. Be aware of your “institutional body language,” i.e. how you may be perceived by others not usually part of your “we.” Nina Simon provides excellent advice in her chapter “Community-First Program Design” in her book The Art of Relevance, which you can read online.

- Look for consistencies and patterns that underlie your previous relationships with audiences.

Is diversity lacking only in your exhibitions and programming? Might the reason be further back in the system, such as in your collections policies and priorities or in the number of diverse staff in positions of power? What steps can you take to address the deeper causes of a monolithic culture at your museum? - Examine the historical record, identifying similar examples over time;

Historical research can animate systemic analysis. Where is your museum located? Does the neighborhood have a history related to red-lining, racial strife, or other tensions that are forgotten (by some) and/or not discussed? Was there ever a period when people of color were not allowed in your museum by law or custom? How recently was this the case? - Appreciate/understand the impact of overarching forces such as culture, the economy, the shifting characteristics of political power, the impact of the media.

Does your museum reflect the various hierarchies of our society, with white men in positions of highest power; women (white and of color) earning less for the same work; full time professional staff mostly white while service staff are mostly people of color? How obvious is this hierarchy to visitors? Have you ever thought about how this institutional body language might affect visitor perceptions and engagement? - Resist one-off solutions that address the surface but not the organism. Do you assess the impact of steps you have taken to address diversity? Have you incorporated measurable goals in your long-range planning? Have you allocated funding and staffing plans that insure sustainability.

Even with systemic thinking, organizational change is difficult

The historic legacies described above live on in specific decisions about hiring, collections, programs, etc, but more importantly they abide in the systems by which museums operate and through which they view the world and their mission in it. These legacies are very difficult to recognize; as a part of the general culture in which we live and breathe, the assumptions on which they are based are mostly unquestioned; they seem to be simply “the way things are.” See post on Museums and White Privilege.

Stepping back to examine the inherited assumptions on which our institutions are based is difficult because:

- it takes time and effort to research and peel back the layers of history

- it will require admitting to some ugly beliefs and actions

- it will involve a redistribution of power, policy, and procedure in our institutions

- It will take time to analyze and connect to current practice: 1)how general legacies of injustice (e.g. Western colonial acquisition and appropriation) might have shaped a collection, and 2) how specific aspects of a museum (where it is located, how it advertises, etc) might affect how the community responds to it .

- Self-examination is often a painful process, even when done privately. But I think that this type of institutional self-examination should be be more public and transparent. It is this transparency, the sharing of experiences and challenges in working toward systemic change, that can help affect the disappointing dynamic that museums have with many communities. The various museum associations in our field could be repositories of museums’ shared experiences.

What are your thoughts about systemic thinking and systemic change? If you are receiving this post in an email and want to comment, please go to www.museumcommons.com. Or send a tweet to me @gretchjenn.

s