In December 2014, in the midst of demonstrations and widespread discussion about race and racism in the aftermath of a grand jury’s decision against indicting a white police officer for shooting an unarmed black teen, a group of bloggers (including this one) and colleagues posted their Joint Statement urging museums to become involved and to respond in meaningful ways. Accompanying the discussion on social media was the creation of the Twitter tag #museumsrespondtoFerguson. Conversations continue in the field, including an expanding Twitter chat held on the 3rd Wednesday of each month. Since I’ve been in the middle of all of this activity from the beginning, I have noticed that the most consistent question or concern raised by museum colleagues is about the relationship between museums’ obligation to #respondtoFerguson and their focus and mission. Do all museums have an obligation to respond? Where do collections and mission come in? These questions have taken a number of forms:

- In December Rebecca Herz published the Joint Statement on her Museum Questions blog, but declined to sign the declaration because she disagreed with the bolded words in the following quotation from the Statement: “Where do museums fit in? Some might say that only museums with specific African American collections have a role, or perhaps only museums situated in the communities where these events have occurred. As mediators of culture, all museums should commit to identifying how they can connect to relevant contemporary issues irrespective of collection, focus, or mission.”

- In her guest post on this blog, about the ways in which the Brooklyn Historical Society is addressing issues of race and prejudice in its community, Director Deborah Schwartz wondered, “As the former Deputy Director for Education at the Museum of Modern Art, I have asked myself what my response to the Eric Garner, Akai Gurley, and Michael Brown cases would have been. Would I have developed a series built around the voices of contemporary artists who are engaged in matters of social and racial justice? Would Glenn Ligon, Carrie Mae Weems, and David Hammons in conversation with activists and journalists result in good programming at MoMA? Would there be a way to engage the curatorial and education staff in issues around whether deconstruction and abstraction both further and hinder our understandings of issues of race and social justice? Equally or more important, would the MoMA audience be ready to participate in any such conversation? Would they have come looking for it? Would such a series be sustainable? Does MoMA have the same mandate that the Brooklyn Historical Society has?”

- In a recent post on the Future of Museums blog, Elizabeth Merritt suggested that encouraging museums to respond to the questions of race and racism raised by Ferguson may lead to inauthentic and naive efforts that risk the of the kind of backlash Starbucks suffered with its #racetogether initiative. While praising the timely responses to Ferguson of the Missouri History Museum and the Newseum, given their missions, Merritt states, “I’m sure there are museums for which addressing race relations in America would be just as awkward a fit as it is for Starbucks.”

What kinds of museums should respond, and how?

The word “Ferguson” has come to stand not so much for a place or incident as for a cluster of events and ideas. The shootings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and other black men by white policemen, the regularity and impunity with which this happens, and the light this sheds on race relations more broadly in the US—Ferguson has come to mean all of this. In my view the story of racism in our country is like a layer of lava bubbling just below the surface. No matter how much we may wish we were a post-racial society, no matter how smooth the cultural surface appears, the burning toxic liquid spills out repeatedly all over the country—racist inside jokes in media mogul emails, fraternity songs about lynching, racial profiling on the highways, and the list goes on. Museums exist in all of the communities in which these events occur. As part of the civic infrastructure of small towns and big cities, museums have a role to play in addressing this original stain of American culture. In my view their civic nature, their grounding in the soil of their communities is more fundamental than museums’ varied missions and collections in terms of an obligation to respond. The focus and format of the responses will, of course, differ according to variables in each community. But I believe that this responsibility does not lie only with museums near Ferguson or focused on current events.

So – What kinds of museums can #respondtoFerguson in authentic ways and how should they do it?

- All museums, no matter their focus or mission, can and should do the following, as suggested in the Joint Statement: “We urge museums to consider these questions by first looking within. Is there equity and diversity in your policy and practice regarding staff, volunteers, and Board members? Are staff members talking about Ferguson and the deeper issues it raises? How do these issues relate to the mission and audience of your museum? Do you have volunteers? What are they thinking and saying? How can the museum help volunteers and partners address their own questions about race, violence, and community?”

- Museums with collections related to American history, whether national, regional, or local. For examples of authentic practice, AASLH stated on December 16, 2014, in support of the Joint Statement:”As our nation grapples with the events surrounding Ferguson, Cleveland, and New York, AASLH encourages all its members to look to their history collections and their position within their communities, and to participate in community healing by providing access to history exhibits programs, and educational materials.”

- Museums with connections to the story of racism in our country: Plantation houses, museums with collections and/or endowments created as a result of colonialism or the institution of slavery. Some of these sites, such as Monticello or the newly opened Whitney Plantation are expressly addressing, in exhibitions and programs, the institution of slavery that was essential to their origins and prosperity.

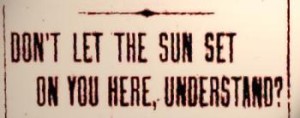

- Museums that were segregated in the past, or that are located in areas that were once “off limits” to people of color, or located in former “Sundown towns” (e.g. Ferguson, MO) where African Americans (and other people of color) could not be seen after sunset. Such museums might want to explore, in collaboration with African American or other community organizations, the history of how their institution or their neighborhood has been viewed by people who were once shut out. This history may be part of the reason for lack of diversity in current museum attendance.

5. Science Museums, especially those that have hosted the traveling exhibition “Race: Are We So Different?”. A number of these museums received training and conducted “talking circles” about race and racial tensions with their communities as part of the programming accompanying the exhibition. Are these types of conversations no longer relevant even if the exhibition has gone? The divisions in the communities probably remain, and the “Race” talking circles could provide a precedent for museum/community conversations related to “Ferguson” as broadly defined above. See also Emily Dawson’s three posts on the Incluseum blog on lack of inclusion in science museums.

We in museums are part of the history of our communities, for good and ill. Given our role as arbiters of culture, we cannot, in my opinion, ignore connections where they exist–geographical, historical, economic, and cultural—with the story of slavery and racism that is so central to the development of our nation. If versions of this national history abide in our community, and if we see ourselves as part of that community, then questions of authenticity go beyond specific mission and inhere instead in civic status. I think it is difficult to ask the question – is our museum connected in any way to this history? Are there resources we might offer? Are there community organizations that might be potential partners, that might perhaps take the lead in addressing these issues? It may be that the answers to all of these questions is no – there is nothing. But asking these questions is essential if museums wish to be and to be seen to be part of the healing process that is so important to the future of our country and of our museums as well.

If you are receiving this post by email and wish to comment please go to www.museumcommons.com or to @gretchjenn on Twitter.

Pingback: Myths and Interpretation | Nicole Deufel's Blog

Very interesting and thought provoking, Gretchen. I used to work at a history museum/plantation and we were encouraged *not* to talk about current events. I understand why–you get plenty of people who are definitely NOT ready to hear that enslaved Africans knew so much…before they were brought to these shores or that it was their labour which built the pretty plantation.

So how *does* one bring in current events?

Sorry to take so long in responding – I had some trouble logging onto my own site for a couple days! I agree it can be difficult at a plantation site. I think unless the whole vision of the plantation takes a turn and there is a willingness to discuss slavery openly, it would be difficult for an individual docent or interpreter to do this. I think if the museum decides to have discussions like this it would need to provide training in constructive dialogue. The Coalition for Sites of Conscience has a number of dialogue training programs. I don;t think this kind of conversation can be taken on lightly or without preparation.

Thanks, Gretchen for continuing the conversation. I’d add one more thing to the first group, particularly based on your highlighting of Deb’s comments. Looking within, for art museums, should include not only staff, volunteers and board members, but also looking at the art/artists that they chose to collect and exhibit.

Yes, Linda, thanks, that is an important addition. G